How Denver Artists Are Rewriting the Terms of Space

Alto Gallery Director Ray Muñoz at Alto Gallery, October 2025.

As Denver’s artists navigate shifting real estate, speculative cycles, and rising costs, they are also building something essential for long-term stability: agency in agreements, in ownership structures, and in how space is shared, stewarded, and protected.

In chapter one of our Breaking Ground: Colorado series we explored the opportunity created by Denver’s downtown vacancies, and in this chapter we move from the macro to the personal. How do artists actually secure space? What agreements make that possible? And what does it look like when artists, not developers, shape the terms?

The answers are emerging not only in Denver’s core but across neighborhoods, collectives, and artist-led hubs. And together, they reveal a powerful throughline. Artist-managed and artist-operated spaces are working and reshaping the landscape in the process.

Artist-Led Agreements as Acts of Agency

Across Colorado, artists are organizing, negotiating, and writing agreements that prioritize long-term stability rather than short-term fixes. CAST’s Managing Director of National Programs, Louise Martorano, has been at the center of helping artists translate their needs into structures that developers can understand.

“In moments like this, CAST’s role really is about bridging the gap,” Louise explained in chapter one. “We support artists as they navigate agreements, advocate for sustainable timelines, and help developers understand why creatives are more than ‘filler tenants.’”

When artists define the terms, something shifts. Risk becomes shared, space becomes more stable, and collective ownership becomes possible where it wasn’t before. The Burrell, home to artist studios, shared spaces, and Friend of a Friend Gallery, is a living example.

As Louise reflected while walking through the space, the agreement there set a new precedent:

“Without an operating agreement that was authored by artists, for artists, over a two-year painstaking process of meetings…nothing like this could have existed.”

That labor, slow, detailed, and often invisible, is exactly what builds agency.

Holding Ground Through Community Partnerships

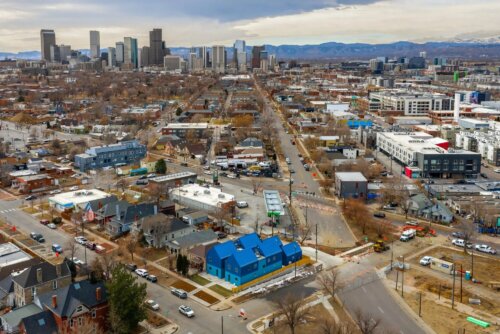

In RiNo ArtPark, Alto Gallery is proving that artist-led spaces can anchor a neighborhood even as the area undergoes intense redevelopment. Director Raymundo Muñoz described how the move to ArtPark in 2019 opened new possibilities, ones shaped by the collective values of the district rather than the volatility artists often face.

“It’s harder and harder to find spaces to have your practice in,” Ray said. “So places like this are so important… and it’s been great here, partly because the district is a lot more hands-on.”

The ArtPark model works because of shared infrastructure and shared purpose, features rarely offered to arts groups in rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods.

“It doesn’t just happen by itself, especially in an expensive city like Denver. We need all the help we can get,” added Ray.

Having that kind of support matters because it also provides structural relief when it comes to operational costs. As Louise described, “[They] don’t pay anything for internet…Denver Public Library extends their internet to Alto and the studios…[They] share a bathroom. [They] have storage in the back for artists. That’s how we can be more affordable when we link arms around collective need.”

These aren’t small details. They’re part of a broader movement toward community-controlled cultural infrastructure and they directly reinforce artist agency to have a more sustainable existence.

Collective Power Rooted in History

At Englewood’s CitySpark, the Los Fantasmas Artist Collective maintains both studio and gallery space. This home that reflects their decades-long mission to create visibility for Indigenous, Chicanx, Latinx, and Raza artists who have historically been treated as “fantasmas,” or “the unseen,” within Colorado’s arts ecosystem.

Having emerged in the late 1990s as a response to exclusion within Denver’s art scene, Los Fantasmas uses its CitySpark base not only to create but to teach, gather, and host intergenerational exhibitions. Their space functions as a cultural anchor, a site where community workshops, youth collaborations, and exhibitions like Raza Futura carry forward the collective’s commitment to resisting erasure and expanding access for BIPOC artists.

Their presence at CitySpark underscores a central truth across Colorado’s creative ecosystems.

Artist agency isn’t only negotiated in contracts, it’s also built in community-owned narratives, shared spaces, and collective imagination.

Los Fantasmas shows what happens when artists define their own terms in both mission and physical space. They’re a living model of artist-driven placemaking that cities urgently need.

A Sustainable Artist Community That Works

In South Denver, TANK Studios stands as one of the region’s strongest examples of a long-term, artist-built solution to affordability. Founded in 2013 by nine artists who literally built out the space themselves, TANK was designed from the start as a sustainable, collaborative approach to shared studio life.

What makes TANK different is not luck, it’s governance. As Co-founder Sarah Wallace Scott described to us, the collective developed a rotational management system where there are always two managers at a time, each serving a two-year role, with one manager rotating out every year so that institutional knowledge is never lost. They act as stewards of the shared studio environment by managing tenant license agreements, gathering and paying collective rent, and staying in close communication with their landlord.

While TANK is proactive in keeping the space functional and safe, the landlord is the one who contracts for repairs. Still, the collective worked closely with him to secure Denver Arts & Venues Safe Creative Spaces grant funds needed to bring the building up to code with the fire marshall. “We work with and through him every step of the way,” she emphasized, underscoring the trust that has developed over time.

That trust is part of what makes TANK work, with an amenable owner that values long-term tenancy working with a collective of artists who demonstrate reliability, transparency, and shared responsibility.

That intentionality is exactly why, when CAST toured the studios, the space felt both grounded and alive. It’s proof that artists don’t just need rooms to work, but systems that honor their natural ability to collaborate, critique, and engage in shared rhythms of practice.

TANK Studios’ success is visible through its longevity, with more than a decade of stability in a city where most artist-run spaces have been displaced multiple times.

Ownership as a Tool for Stability

If TANK reveals what artists can build through cooperation, Friend of a Friend Gallery shows what becomes possible through collective ownership.

Co-Director Derrick Velasquez has been building artist-run spaces for nearly two decades, including being a founding member of TANK. He has opened DIY galleries in communal houses, curated exhibitions in basements, run pop-ups in warehouses, and transformed empty corridors of historic buildings into cultural gathering points. By the time Friend of a Friend found a home in the Evans School in 2021, he had already spent years imagining what a permanent, artist-owned space could look like…and why Denver needed it.

But the path to ownership wasn’t easy. “For years it was the same issues: lack of space, lack of affordability, lack of opportunity. It becomes pretty simple…but the forces behind it aren’t simple at all,” Derrick told us. “A lot of the city has been bought up by outside entities…no one owns it, so no one even looks at it, and no one even cares about it.”

Against those forces, Derrick and a small group of artists spent nearly a decade trying to pool resources to buy even the smallest commercial parcel they could find. Often, they were outbid. Often, the math didn’t work. And often, the buildings available were too large, too expensive, or designed only for retail tenants with far more capital.

Still, they persisted. The breakthrough came when Ana María Hernando, then an artist-in-residence at RedLine Contemporary Art Center, joined the group. Her commitment and investment made it possible to purchase the commercial space in the Burrell building outright, without relying on predatory lending or risky debt structures.

The Burrell presented a unique opportunity where a willing affordable housing developer was looking to fill their ground floor commercial space, specifically someone who could also honor the legacy of the neighborhood’s artistic origins (the building’s namesake is in honor of jazz musician Charles Burrell). Having that alignment around the cultural value of the arts and the desire to maintain its presence, along with an intermediary like Louise championing the deal, helped make the case for Derrick, Ana María, and the other artists who banded together to purchase the space.

Derrick described the moment simply, “If we didn’t do it then, we may never have done it.” And when Ana María stepped in? “She came in at the last minute, said yes, and put up the rest of the cash. That changed everything.”

Together, they designed the space intentionally, half for Ana María’s studio and half for Friend of a Friend Gallery. Derrick created a layout that honored both uses, while ensuring the gallery remained small enough to be run sustainably by a team of working artists with full-time jobs elsewhere. The result is more than just a gallery. It’s a proof of concept.

As Louise noted, “If we can actually create a trusted community to help broker…there’s so much that sits outside what feels familiar. How do we create more of these bridges to industry that artists are actively contributing to, but not actually a part of?”

Her words underscore that ownership isn’t simply about buying space, it’s about building the structure, trust, and partnerships that make artist-led real estate possible in the first place.

Building the Structures Artists Need and Deserve

Walking through her studio, artist Ana María Hernando speaks with clarity about why structures matter.

“For artists, we need to make a structure where life becomes affordable,” she said. “We bring gifts to society, and society enjoys this, but when it becomes about property, then we are out of it…I’m all for trying to make real estate a possibility for artists to buy.”

Her insight cuts to the heart of this chapter. Artist agency is impossible without artist access to space, whether through ownership, long-term agreements, or shared governance.

Ana María described how vital it was to craft agreements collectively with other artists at the Burrell:

“Each meeting, I would read the same paragraph again and again…but we are promoting practices that work for us.”

The process was slow, imperfect, and deeply human, yet it produced a stable base from which artists can work, plan, and dream. Her participation in shaping the operating agreement was not symbolic, it was an act of agency, one that directly determined whether she could continue working in Denver. She summed up the urgency simply: “If I didn’t have a space to work, I couldn’t be in Denver.”

Ana María also reminded us that shared structures don’t only make space possible, they make the work more sustainable. “We are more used to being on our own…When you can do things as a group, it’s so much better. Not only [because] of the division of labor, but it’s the coming together of more brains…you can lean on each other.”

Why Artist Agency Matters Now

Across interviews, site visits, and conversations, one message came through consistently.

The cultural future of Denver and many cities like it depends on artists having real say in the agreements that shape their spaces.

As CAST continues our work in Colorado, these stories offer a roadmap for what comes next. Artist-operated spaces are proving they can succeed not as temporary activations, but as long-term community anchors that bring life, stability, and creativity into neighborhoods. At the same time, collectives and cooperatives are rewriting the rules of ownership and access, demonstrating that agreements authored by artists themselves can create stability that traditional development models rarely achieve. Partnerships that intentionally share costs, space, and responsibility are making affordability real rather than aspirational, while city-led efforts are showing the most promise when they align with artist-led structures rather than asking artists to adapt to preexisting frameworks.

The opportunity in Denver isn’t only the seven million vacant square feet downtown. It’s the chance to deepen, replicate, and sustain the artist-driven models already working across the region.

Read the series

This is an ongoing series following CAST’s expansion into Colorado. Follow along for the lessons we’re learning as we develop affordable space opportunities for and with artists and creatives on the ground.

- Securing Space

Breaking Ground: A New Chapter in the Rockies

This next chapter of Breaking Ground follows CAST’s expansion into Colorado, where we’re deepening our focus on affordable space for arts and culture.

- Securing Space

Denver’s Downtown at a Crossroads

A look at the transformation of downtown Denver, where post-pandemic vacancies are creating a rare opening for creative reuse.

- Stewarding Space

When Home and Studio Become One

How live-work and proximity-based models for artists are creating the conditions for creative stability, community connection, and long-term opportunity.